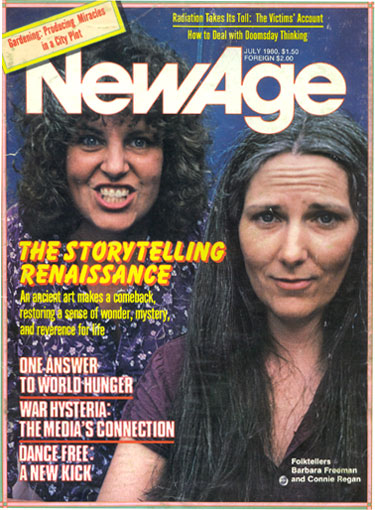

- Written by: Rex Weyler – New Age Magazine

“…The storytellers’ art is an ancient one, passed from old tongue to young mind, from the fountainhead of culture and history… ”

Once,” says Barbara Freeman, face all alight with sun and wonder, driving through the White Mountains of New Hampshire on a spring day in 1980, “long ago” – and so stories have always begun, invoking a fundamental lore deeper than any record, a mystery more profound and subtle than any that could be captured by the relatively crude mechanics of written and dated history – “there were two brothers… Now, this is a true story…”

“Every story has some truth to it,” adds Connie Regan, looking out the window, “although some of the details may be lost or changed from culture to culture. What makes a story a true story… Hey! Look! Whoa, look at that purple coat’! Hey, Barbara…” The car slides to a stop on a country road in front of an old farmhouse with a big “Used Clothes” sign out front. The two women disappear into a barn filled with remnants and antiques from which they will not emerge for an hour.

I sit in the sun scribbling notes, knowing that the notes won’t be much help later when I try to figure this out. There’s a mystery here. Connie Regan and Barbara Freeman are storytellers, The Folktellers by name, and their art is an ancient one, passed from old tongue to young mind, from the fountainhead of culture and history.

The Roots of Storytelling

Folk tales grew out of the rich tradition that followed Homeric epics and ballads, Roman legions, Viking raiders, and Gypsy lore throughout Europe, giving rise to the Anglo -Saxon stories of Beowulf and the Canterbury, Tales. From this same tradition grew the Cymric school of bards in Wales and the Gaelic school of ollamhs in Ireland. Storytelling became a high art, and ollamhs the keepers of genealogy and history; the techniques of composition and telling, as well as tales themselves, were passed down from master to apprentice.

To the seanachie, one of nine divisions of ollamhs, fell the responsibility to keep and transmit the historical tales. A seanachie apprentice was required to learn 178 traditional stories of common and royal history. The heroic sagas, or loidhes, were metered, rhymed, and chanted by the seanachies in the eerie Gaelic minor scale of five notes. The seanachies, it is told, learned their skill for song from the banshees, female spirits who wailed warnings of death. This tradition, alive with leprechauns, elfin kings, heroes, and children, was brought to North America by Irish immigrants during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Carried across the ocean to the New World, the seeds of Old World lore took root in the Appalachian Mountains, from Nova Scotia to Alabama, and eventually spread throughout the continent.

Ruth Sawyer, author of The Way of the Storyteller (Viking, 1942; Penguin, 1977) was fortunate to grow up under the care of one such traveler, her nurse, Johanna, who came over from County Donegal in the 1880s. Becoming a storyteller herself, Sawyer would one day write: “Thrice blessed is that child who comes early under the spell of the traditional storyteller, one who holds unconsciously to the ancient and moving power of her art. I was such a child. No fairy godmother could have hung over my cradle with richer gifts than Johanna, my Irish nurse. The blood of the old seanachies ran in her veins. “I can feel the comfortable refuge of her lap. I can see her face, fairy- ridden. I can hear the soft Irish burr on her tongue which made the words join hands and dance, making a fairy ring that completely encircled me.” Storytelling is a sacred art, a living art passed on from teacher to Student, parent to child, master to apprentice, through a shared experience. Throughout her career Ruth Sawyer taught would-be storytellers to honor the rich inheritance of the art with “integrity, trust, and imagination.”

The Folktellers are cousins whose families settled in the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and Alabama. As a young girl Barbara lived in Nashville, Tennessee, while Connie’s family moved to Florida, but they spent the summers together riding horses, running through great green fields of grass, swimming the river, and listening to their fathers tell Irish jokes that had passed down through the families from further back than anyone could remember.

Barbara Freeman was born in Nashville on November 2, 1944. “No one in my family really told stories,” she says, “but my father told jokes, old ones, and I thought they were funny. Then one day I saw Martha Raye on television, and I remember laughing and thinking, ‘That’s great! That’s what I want to do!” I wanted to make people laugh, and I knew I could do it. I knew that if I went and knocked on her dressing room door, she’d hire me on. Then later I saw Lily Tomlin and I realized that making people laugh was only part of it, that it was also important what you said.”

Connie Regan was born in Mobile, Alabama, on January 20, 1947. “My father,” recalls Connie, “was a lover of the English language, and he told Irish tales. I remember also being very impressed by Hal Holbrook as Mark Twain.”

Martha Raye? Hal Holbrook? Leprechauns? These two women definitely weave a special magic in their performances – Barbara always quick with a joke, Connie able to still the rowdiest crowd with an eerie mountain tale – but it isn’t simple entertainment that they offer. The mystery haunts me.

Boom! Out of the old barn like an explosion twirls Connie in a new sky-blue skirt, and behind her Barbara, with arms full, beams and chatters. “Owww, what a lovely day! Chauffeur? Chauffeur? Quick, we must hurry; there might be another antique shop down the road…” We’re on our way to Brattleboro, Vermont, where The Folktellers are scheduled to perform at a coffeehouse. I sit in the back seat, hot wind whipping in through the windows, old brown wooden boxes with neat little brass latches, unnamable artifacts of the road, dog-eared storybooks falling from the pile of old clothes worn by who knows who or how many healthy country women.

“Connie and Barbara learned something more important than the stories themselves: they learned to love the telling…” “. . . So what makes a story true,” continues Connie, surprising me, picking up right where she left off as if the hour in the old barn had been only an instant, or the whole thing had been a flash of imagination,”are not the details, but something that lies under the details, not like a ‘moral’ or a ‘message’ or anything like that – a true storyteller never says, ‘And the moral of that story is. . .’ – but something even deeper than that. You see, it’s like people always ask us, ‘How did you get into this?’ Well, it’s not really something you decide to get into, it just sort of happens.”

“Yeah,” says Barbara, “it’s not like you say, ‘Oh, I guess I’ll go to college and be a storyteller.’ “

“So,” I ask, a bit hesitantly, “how did it happen?”

Becoming Storytellers

These two quite remarkable women were once adventurous young girls. Both traveled out west as teenagers to work and to see what they could see. Connie worked as a, waitress at the Broadmore Hotel in Colorado Springs, and Barbara worked as a tour guide At Yellowstone National Park. Later back in Tennessee, Connie joined Barbara at the Chattanooga Public Library, where, in addition to many other duties, they told stories to children. Barbara at the main library, while Connie toured the daycare center’s showing films, performing with puppets, and telling stories as “Ms. Daisy.”

In the early ’70s, after the country had exploded in protest over the bombings in Cambodia and the killing of students at Kent and Jackson State Colleges, both Connie and Barbara joined and worked on the steering committee of the Chattanooga chapter of the National Organization of Women. “We toured clubs and organizations,” says Barbara, “talking about women’s rights. You can imagine,” she laughs, “the level of awareness about women’s issues in those days at the Chattanooga Kiwanis Club or the Saratoga Sunrise Breakfast Club! Whew. You know,” she mimicked, hunching her shoulders and snarling, “‘ask one of the girls at the desk to help you.’ “

“We learned that terminology is important,” explains Connie, “that words do make a difference. This carried over later in our selection of stories.” It was at this time that they learned many of the traditional and modern tales that still make up a large part of their ever-growing repertoire. They also learned something much more important than the stories themselves: they learned to love the telling. Not reading, but telling stories became a focus for their lives, a duty, the one thing they loved to do, individually and together.

In 1972 they took a trip to the Folk Festival of the Smokies in Cosby, Tennessee. “This was the first time,” recalls Connie, “that we had heard music presented like this, at a gathering. The atmosphere was – amazing! I have such a vivid memory of that feeling: that if there was any way I could earn a living traveling around to these festivals, I would do it. Anything!”The following summer they went to the First Annual National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee. “The festival was organized by Jimmy Neil Smith,” explains Barbara. “He got the idea while listening to a story on the radio, so the joke is that the National Storytelling Festival was conceived in the back seat of a Chevy!”

That first storytelling festival was the last time either of them would be just part of the audience at any such gathering. The next summer, in 1974, Connie went back to Jonesboro a month early to help set up the festival grounds, to hang around and to see who she could meet. Sitting by the campfire one night, someone asked her what she did. The answer just burst out of her: “I’m a storyteller. And, uh, so is my cousin Barbara – she’s coming up next week.”

“Well, you should tell some stories on stage,” suggested someone in the circle.

“Follow me!” said a lively woman in a black cape who led Connie through the black night like the embodiment of mystery itself. “My name is Carolyn Moore; you should meet Jimmy Neil.” After they had talked for a while in his office, Jimmy Neil reached down into a drawer and pulled out a soiled manuscript. “You’re just the woman I’ve been looking for,” he said, handing her the manuscript. “Here, this story comes from Coffee Ridge. It’s true; it was written down by an old woman named Elizabeth Seeman. Read it. If you like it, maybe you can tell it at the festival.” The story, “Two White Horses’,” was the most haunting and powerful story that Connie had ever heard. After reading it, she knew she would tell the story at the festival, that she would be a storyteller, that she would tell stories to adults as well as to children. She phoned Barbara and told her to come to Jonesboro as soon as she could; they were going to be on stage this year. When it came time for them to perform, they were too excited and determined to be nervous. They told some of the children’s stories that they had collected at the library, some mountain tales that they knew, and then Connie told “Two White Horses.” There was a magic in their performance, a balance, wit, charm, humor, seriousness, they were a hit.

As they came off stage Jimmy Neil Smith introduced them to Elizabeth Seeman, who had been in the audience. “Well, Connie,” said Elizabeth, seventy- five years old, bright-eyed mountain woman, “you did right well. Now, I may have written down those words, but that is your story.”

“…Their tandem approach worked like magic: they howled, hooted, and held the children spellbound…”

Back in Chattanooga, the two librarians began to save their money. By July 1975 they had saved $2,000, outfitted a Datsun pickup truck – nicknamed “D’Put” – with a camper, quit their library jobs, and had taken to the road. They hadn’t had time to arrange bookings for that first summer on the road, so they bought two tickets to the Fox Hol- low Folk Festival in Petersburg, New York, and headed north, figuring that something would work out.

Tomorrow, the World

Arriving in Petersburg they pulled into the campground and picked a good spot down by the river. The place was jammed with people. How, they wondered, would they ever find the festival organizers? The backstage area was fenced off, and everybody and their dog was trying to get back there. After the first day of the festival Connie and Barbara went back to D’Put and went to sleep. Connie awoke at 4:00 A.M.: someone was shaking the truck and hollering: “The river is flooding. You folks better get up!” Connie looked outside: little D’Put was up to her hubcaps in water. “Barbara!” she cried out, “the river’s risin’! The river’s risin’! Barbara, wake up!” “Oh,” grogged Barbara, looking out, “Hum, yeah, wow . . .” and she rolled over, back to sleep. Connie got dressed and drove D’Put to high ground. A festival worker met them at the top of the hill. “All you people who got flooded out down by the river,” he waved to them, “come over here to the performers’ area where there’s some room for you to camp.” When they awoke the next morning, they were out of the flood and into a sea of fiddlers, pickers, singers, and folk world heavies. “Wow,” said Barbara, “what happened?” Connie laughed, “You wanted backstage, didn’t you?”That evening they sat around the campfire with some of the performers and joined in the storytelling. “Hey,” said a woman in the crowd, “you two should go to Hartford! Caroline and Sandy Paton are going to have a storytelling workshop there.”

So, later that summer D’Put chugged into the festival parking lot outside Hartford, Connecticut. As the two storytellers sat on the back of their truck, a crowd of kids gathered around. “What do you guys do?” asked one of the boys. “Are you musicians?” “No,” said Barbara, “we’re story- tellers.” “Tell Where the Wild Things Are!” “Well, okay,” said Barbara, “but first, open up your closets … Creeeeak,” as a dozen children opened up their imaginary closets, “and put on your wolf suits!” “‘Cause that night Max had his wolf suit on . . .” chimed in Connie. It was the first time that they had ever told Maurice Sendak’s story together, though they had each told it to library children many times. The tandem approach worked like magic: they traded lines, acted the parts, howled, hooted, and held the children spell-bound, Sandy Paton managed to squeeze them into the program, just before Gordon Bok, the well-known singer, songwriter, and storyteller from Maine, was to appear. “Oh, my,” thought Barbara, “we’re gonna get tomatoed! These people are waiting to hear Gordon Bok, and here we come, total strangers.” But the crowd loved them. They told some mountain tales like “Wicked John and the Devil,” introduced Wild Things in their new style, and left the stage under a thunder of applause.

Backstage, they were mobbed with job offers and suggestions of people to meet. Bob Zentz invited them to the Old Dominion Folk Festival in Norfolk, Virginia, and Bill Domler booked them into a Hartford coffeehouse, the Sounding Board. Domler took them in hand: he introduced them around, wrote to people throughout the folk world recommending them, and, for the coffeehouse date, took them to a photographer who made their first flyer. Not yet “The Folktellers,” – they called themselves “Barbara and Connie” at one place and “Connie and Barbara” at the next.

After Hartford they never again had to count on rivers flooding to get backstage, their talents became well known by word of mouth throughout the folk community. They played a lot of middle sets and free shows that first summer, and, after exhausting their savings, went back to North Carolina for the winter. Meanwhile, their names flowed along the grapevines of folkdom.

The following year they were back at Fox Hollow as performers, and with a dry campground. They were paid $500 to present a two-day workshop for the libraries of Kingsport, Tennessee; they played the Smithsonian Folk Festival and the National Bicentennial Folk festival in Washington, D.C.They were flying to performances now. Though still not making much money after, all their expenses, they were breaking even and feeling good. They’d been blessed, getting to do exactly what they wanted to do. With all their worldly goods packed in their camper D’Put, they were free – or so they felt till they got to Atlanta.

Returning to their camper after their performance at the Atlanta Folk Festival, they discovered that D’Put had been broken into, their belongings pilfered. Their hearts sank as they stared into a ransacked, empty D’Put. Gone was their money, tape recorder, tapes precious and irreplaceable, personal journals, quilts, and their banjo. “Ants!” screamed Connie. “Ants! They should be buried up to their necks in the desert by an anthill, with honey all over their heads. Thieves! They should be eaten by ants.” Barbara grabbed her by the arm. “Hold on, it’ll be all right. There’s nothing we can do about it now anyway. Just calm down. It’s all’right, we’ll figure something out.” Barbara crawled in to check the damage, went through what was left of their clothes, and discovered that her overalls were gone. “My overalls! They took my overalls! Ants! Ants! Ants!” They sat on the back of poor D’Put and cried.

“…They were flying now. Though still not making much money, they were getting to do exactly what they wanted to do…” But now they were really free – with no home, no belongings, no money, just D’Put and their stories. It was a turning point for them; they had to start all over, and they were more determined than ever. They took a new name, “The Folktellers,” made it through the summer paying for their travels with the small fees they earned, and returned to Asheville poor and proud.

In 1977 they taught a credit course for Pace University in Westchester, New York, and gave workshops for the Catholic Library Association in St. Louis. When they performed at Saint Bernard Academy, Barbara’s Nashville high school, they received a standing ovation, their first. It was a big night for them, sort of a homecoming. Later, at the thirty-sixth annual Chicago Folk Festival, they were called back on stage for their first encore. They were beginning to feel like professionals.By 1978 they were doing 150 programs a year, including workshops, festivals, high-school performances, library story hours, concerts, and benefits. They were making money now, and the world was opening up to them. That summer they traveled north to the Winnipeg and Mariposa folk festivals. At Mariposa they met a man who would introduce them to an entirely new realm of storytelling, Ron Evans.

Evans was a Métis, French and Chippewa Cree, from northern Saskatchewan; he told traditional tribal stories of the “Trickster Hero,” the personification of the Creator/Destroyer in Cree spiritual teachings. He shared with the Folktellers ancient and historical stories of his people, including the history of Luis Riel, who fought the English for the liberation of the Métis. He planted within their rich garden of lore the seeds of Native American Indian culture.

The Folktellers’ perspective was broadened further by a trip to England in the summer of 1979 for the twenty-fifth Sidmouth Folklore Festival: while in England they performed at libraries, coffeehouses and pubs, picking up new tales along the way. Then they returned to tour Texas, California, and to attend the Rocky Mountain Healing Arts Festival high in the Rocky Mountains outside of Boulder, Colorado. It was here that I first heard them.

“Howdy, y’all,” chuckled Barbara on the first evening of the festival. “We’re the Folktellers, and we’re from Asheville, North Carolina. Any y’all ever been to Asheville? No? What’s a-matter with you? Well, that’s all right. “Anyway, I know you’ve come here to work on your yoga and T’ai Chi an’ all that, but I thought maybe I’d catch ya up on the latest about ol’ Dry-Fry – surely you’ve all heard of ol’ Dry-Fry, haven’t ya? Eeeeeeverybody’s heard of ol’ Dry- Fry!”Well, Dry-Fry’s an old preacher, but he’s that kind of preacher that only preaches for the,” rubbing her thumb and forefinger together in front of her nose, “you know, the big bucks! Well, maybe you haven’t heard the latest about what ol’ Dry-Fry’s been up to, so I’ll tell ya. Last I heard, his bicycle’d come up missin,’ and ol’ Dry-Fry was fit to be tied, lookin’ for who it was that stole his bicycle.

I sat spell-bound with the others in the room as the two women told tales that made us laugh or gasp as the mountain wind rattled the windows now and again through the night – right on time, always, as if the tellers were in touch with the elements themselves. I was sorry when it was over; I wanted them to go on forever. During the week that we spent in the mountains with herbalists, physicians, musicians, psychics, therapists, and healers of every persuasion I never once missed an evening session of storytelling, and I felt most honored to make the acquaintance of The Folktellers. They were, among all the wonderful and richly gifted people there, the one unifying factor, the most universally healing influence, the one hand that reached out to everybody, mystic and scientist, young and old. Their touch was deep.

One night toward the end of the week, after stories, we sat in the moonlight late and talked. “This is a good experience for us,” said Connie. “We don’t meet these kinds of people at folk festivals and libraries. It’s very different; I’m learning a lot about a whole new way of thinking. I can see a tie between what we are doing and the whole idea of healing, of wellness. “It’s like Ron Evans told us: Stories are sacred; you have to treat them with respect. Ron says that when you let your breath out – when you talk, tell a story – you are letting your children out of your body, you are releasing your children. That means that you have to be very careful, you can’t just let your children out anywhere under any circumstance.”As we travel, we can see the moods of people. We just try to share something positive and loving.”

The Art of Storytelling

Passing now through Hillsboro, New Hampshire, heading southwest to the Connecticut River (it has been a year since we waved goodbye in the Colorado Rockies), I am beginning to understand what Connie and Barbara mean by the truth and sacredness of stories; I am beginning to sense the significance of the storyteller in this modern culture dominated by giant entertainment industries, where a story is judged by its box-office receipts or Nielson ratings.

We’ve just come from a librarians’ workshop held in North Conway, New Hampshire. There the Folktellers stood before a buzzing assembly of librarians, young and old, from towns and cities throughout New Hampshire, and told “The Brave Little Hunter,” a participation story for young children. As they listened, a hundred librarians slapped their laps, swam imaginary rivers, sloshed through mud, saw a deer, got frightened by a bear, and scurried back, double-time, past deer, through mud, river, forest, and safely back to their cabin. After performing, Connie and Barbara had talked to the librarians about the art that had become so central to their lives. “… ‘Stories are sacred. As we travel, we can see the moods of people. We just try to share something positive and loving’ …” “There is an important difference between telling a story and reading a story out of a book,” Connie explained. “By putting the book down, you open up the imagination of the child, you let them draw the pictures with their fertile minds. As children get older, storybooks lose their appeal, they think it is something for little kids, but you can still capture their imagination by telling stories.”

“We suggest,” offered Barbara, “that you learn the modern stories word for word, and learn them well. Traditional stories change and vary from place to place, but if you make changes in them, do so with a gentle hand. Remember, stories are very subtle: it is only after many years, sometimes, that we see the meaning and get a sense of why a story is told a certain way.” “The most important thing to remember in learning stories to tell,” said Connie, “is that you must love the story. Don’t try to learn a story that you don’t really like; it is useless. You must love the story so that the story can become a part of you. Thus, it always gains something in the telling because you have put your heart into it. Once you learn a story well – you may have to read it over fifty times – you will always have that story with you; it is something that you will carry with you all your life. “And remember,” she added, “as we storytellers get older, we only get better. The stories grow inside us; we become more credible, more subtle, wiser, and the stories gain in richness. As an eighty- three-year-old storyteller from Michigan told us, ‘If you learn just one new story a year, by the time you’re my age you’ll know a lot of stories, won’t you!’”

From North Conway we have traveled east along the Swift River and over Kancamagus Pass in the White Mountains. We drove south along the Pemigewasset to the Merrimack River, singing, telling jokes, and ancient tales of how the sea got its salt, how dogs came to hate cats, how big man Jack killed seven in a whack, and this is a true story – how two young country girls of Irish blood rose on a flood of ancient lore to become storytellers, magicians of emotion, jugglers of smiles and tears, reminders of what is precious in these loud and electric decades of the late twentieth century.

Performing at the Coffeehouse

In Brattleboro, Vermont, on Friday, May 16, 1980, I sit in the shade of a blossoming crabapple tree with The Folktellers – our last chance to talk before their evening performance at the Chelsea House. I ask them about their performances, their balance of humor and seriousness. “At first,” confesses Connie, “I was uptight about Barbara’s jokes. Sometimes I thought it was too much, sometimes during a performance when everybody was laughing, I felt real bad. There was too much of a polarity, I felt – it was going away from storytelling. I struggled with these feelings.”

Barbara: “People would tell Connie, ‘Let Barbara go, don’t hold her back,’ but it was necessary for us to struggle to find the balance. Connie would get people in a certain mood, and then I’d always break it with some one-liner, but you have to be careful. Jokes are okay, but I found that I had to use restraint. What we have now works, but if we get too far from the harmony, we have discord, we lose the magic.”

Connie: “Maintaining a mood is important. It has been painful sometimes, working for the right balance, but we always knew we could do it.”

Barbara: “People love to laugh, but they also love to feel things, to feel sincerity or intensity. Scary stories for instance, are not really for the scariness, but for the tapping of emotion. People really like those stories, it makes them feel good.”

Connie: “Real sharing is the sharing of deepest human experience – sharing of emotions, the whole range. If you only laugh, you have nothing to compare your laugher to; if you only love, you have nothing to compare your love to. It is necessary, if we are to grow emotionally, that we learn to see the many sides of our inner selves, to share those inner feelings and urges, because they reflect what is really essential, not only to our personal growth but also to our collective cultural growth.”

The Folktellers return to the Chelsea House; I wander through town to the west bank of the Connecticut River, where I find a weather-white log suitable for sitting and thinking. I recall how D. H. Lawrence warned that the twentieth century would “bury the delicate magic” of its cultural heritage; how Carl Jung admonished modern humankind as “poor in spirit because they no longer live a symbolic life.”

At the same time that we’re experiencing an electric information explosion which is maybe invidiously, sometimes benignly, or even adroitly and gloriously global, there is an organic, nourishing implosion happening, a movement toward sustainable, decentralized survival and wellness of person, community, and culture. Storytelling reemerges in this environment to reclaim its place as a personal and cultural healing force. Cultural media either run deep or they run dry; the river outlives the state. ‘Styles, fads, network stars, electric flashes of instant global identity are simply not the stuff of which culture is made.

Culture is simply that – culture: it grows; it is organic. And the oral transmission of knowledge, of behavioral styles, of truth – “Every story has some truth to it” – lives and flourishes because it involves an organic process: the knowing, telling, hearing, and visualizing of information. “ … ‘People love to feel things. Stories are for the tapping of emotions: they make people feel good’…” As the Irish storyteller Ruth Sawyer writes in The Way of the Storyteller – “Memory is a pleasant and profitable performance of the mind, so is intellectual appreciation. These as compared to the imagination, however, are but pale and sterile. It is your imagination I would conjure, and your emotions, to touch your heart, so the mind may know.”

That evening the Chelsea House is abuzz with excitement. Local musicians play and sing while the Folktellers listen and wait graciously for the stage. Then, taking the stage, they slowly begin to weave their special magic. As the evening passes, we, the listeners – held in trance, dashed with a joke, then stirred with wonder and excitement – grow finally quiet as we hear the story of the Mountain Whippoorwill, of the fiddler who fiddled ’til he cried, and the old fiddler who grew too sad to play after losing his young bride. And when they finish with their last great tale, we explode and applaud them back on stage for one more story. Well, they decide to tell an old story of a mother whale who lamented for her young. As I wait in the dark for the story to begin, Connie calls me up to the stage, saying: “Do you have your flute? Can you play a whale singing for this story?” “Uh, sure,” I say, though my stomach feels weak and I’m nervous to be stepping up on a stage to play before people, even with the cover and help of the Folktellers. But I do it, pulling a chair to the side and a little behind in the dark, and they began their tale. When they come to the part about how the mother whale breathed, I make a little breathing sound through the bamboo flute, and when they come to the part about how she cried, I try to forget all about the people and the stage, so I close my eyes and there imagine as best I can a real crying mother whale; I can feel the cry swell up from deep inside, and I know that these Folktellers are giving me a lesson, teaching me to share something, and though I feel a little scared, I blow real soft and hear the whale cry fill the room. I feel suddenly close to everybody; then it is over. Outside in the dark night the moon has already fled the starry sky, but Jupiter still chases Mars, and way over in the east, Saturn awaits them both. Under all of this we hug and – feeling a little silly and embarrassed – say how much fun we’ve had and how sorry we are to be splitting up. We dance a bit and swing in the road holding hands, laughing. I drive off toward the city, singing to myself all night on the road. That was the last I saw of them, jumping and dancing and waving in the moonlessness, but from what I hear folks tell, they are still a-wanderin’ and doin’ right well.

The Folktellers will appear at the following festivals the summer of 1981:

July 18-20: Vancouver Folk Festival, Vancouver BC

July 22-24: Black Hills Survival Gathering, Rapid City SD

August 8-10: Augusta Folk Festival, Augusta GA

August 22-24: Philadelphia Folk Festival, Philadelphia PA

October 3-5: National Storytelling Festival, Jonesboro TN

For further information on these and other events, contact the National Association for the Preservation and Perpetuation of Storytelling, 116 West Main, Jonesborough TN 37659