- by Barbara Home Stewart, a free-lance writer, lecturer, and former newspaper and magazine editor – School Library Journal

- ©1978 Barbara Home Stewart

The Folktellers invite the audience to join them “Where the Wild Things Are”

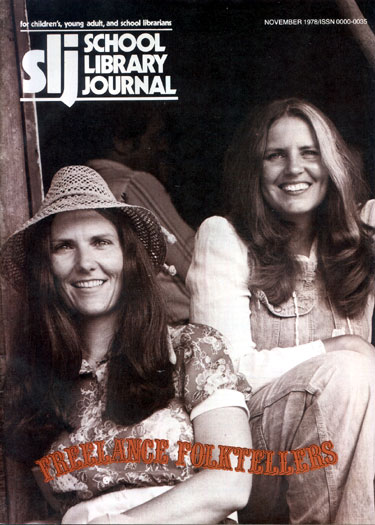

My first close encounter with Barbara Freeman was in 1973 when I visited the Chattanooga Public Library in Tennessee in search of a feature story for the Roadrunner’s Report, a library service department newsletter which I produced for J. B. Lippincott. Speaking to her was an experience. I knew at once that I was in the presence of a new kind of solar energy. Listening to her nonstop, mile-a-minute conversation was like standing next to a grindstone and watching the sparks pop off in all directions. Her sparks were ideas and they were generated by her desire to make children aware of the power of books.

On that first visit I knew I had met a true mover and shaker of the library world. With innate artistry and determination, Barbara Freeman had transformed a dull, dingy, old Carnegie library children’s room into an enchanted underworld. A 30-foot plywood storytelling castle was standing across one corner of the room. In a single craft day held in the castle (which was guarded by that knight in tarnished armor, Sir Read-a-Lot, cousin to Lance) over 100 children jammed inside the plywood haven. Outside, another 100 watched a film while waiting for their turn to enter. The ingenuity of Barbara’s programs and the audacity of her approach to children’s literature most likely were influenced by her background as a horseback riding instructor, lifeguard, bus girl in Yellowstone National Park, and her years of teaching seventh grade students before earning her M.L.S. degree.

So in 1975 it was no real surprise when I received a phone call from Barbara telling me that she and her first cousin, Connie Regan, had quit their library jobs, pooled their life savings of $2000, and gone on the road as “The Folktellers.” Amid a tumble of words, Barbara brought me up to date on happenings. My excitement grew as I learned more about Connie. “Connie has a creative streak a mile long. From 1972 to 1975 she was coordinator of an outreach library program she named M.O.R.E. (Making Our Reading Enjoyable). And with the storytelling name of ‘Ms. Daisy,’ Connie took films, puppets, tales, and lots of love and talent to Chattanooga’s children in day-care centers. We both loved our jobs, but we’re going to try to make it on our own.”

Barbara continued, “We both realized that our storytelling was a doorway to the imagination for both youngsters and adults. In some cases, it was an avenue to experiences that couldn’t be provided by books on a shelf. We began thinking that the storytelling itself, – the telling, listening, and the sharing – might have a valuable meaning for many people outside the reach of the Chattanooga Public Library. So, we counted up our assets, pooled our pennies, and took the plunge . . . “

Although I never had a chance to travel with them or share their experiences, I was able in a small way to feel that I had been a part of the journey. On a week’s advance notice of their arrival in Philadelphia that spring, I invited 15 school and public librarians to my home to meet “The Folktellers.”

“Barbara (above) changes voices for different characterizations and uses a wide variety of facial expressions and gestures. Connie (below) uses the full range of her voice, with all its lyric highs and somber lows.”

As these two storytellers unfolded tale after tale, the brick walls of suburbia melted away like the walls of the attic where the magic godmother lived in George MacDonald’s beloved The Princess and the Goblins, and for a few moments, the dinner guests were lost in another, faraway world . . . a world where a ghostly image of a woman who was buried alive floated through a misty countryside as two white horses neighed in greeting; a world where wild Sendakian things grew larger than the pages of a children’s book as Max’s ghoulish comrades loomed over us in the dark shadows of our imaginations.

When the last folktale was over and we had returned to reality no one spoke for a moment – and then everyone spoke at once.

“When can you do a program for the Free Library and the Catholic Library Association?” asked Carolyn W. Field, coordinator of children’s services at the Free Library of Philadelphia.

“How much lead time do you need for bookings?” asked assistant coordinator Helen Mullen.

“Do you have special programs for preschoolers?” inquired Beatrice Kalaminsky, former president of the Philadelphia Association of School Librarians.

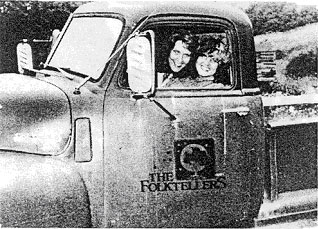

“Can the children see your pickup truck D’Put?” asked Marian Peck, Norristown children’s librarian.

“How can we reach you when you’re on the road?” questioned Dorothy Stanaitis, children’s librarian at Gloucester Public Library in New Jersey.

And so it went – until we all ran out of questions and the clock ran out of time. But in the months and years to come, The Folktellers realized many profitable engagements from this initial introduction to Philadelphia’s friendly librarians.

The next morning, however, at the breakfast table, my “helping hand” took the form of a figurative slap on the two women’s wrists when we began discussing their very modest fees. After we analyzed their current rates, they quickly saw they were earning only pennies an hour-after subtracting food, shelter, car maintenance, promotional brochures, postage, and so on from their fees. That morning at our kitchen table proved a financial turning point. Phone calls from both Folktellers over the next several months related their surprise and delight that sponsors did not “blink an eye” at their updated fees, which are still, by modern standards, very moderate.

“The first year,” Connie related, ‘we cleared all of $400 after expenses. The second year we did a little better. And believe it or not – this third year we’re actually going to have to pay income taxes!” “We’re pleased with how we’ve worked out our fees,” Barbara continued. “We charge $500 for a festival weekend, $300 for a concert performance, and $100 each workshop hour. We are still keeping our school rates low – around $100 a program. There is also a transportation fee depending on our expenses.”

“When we first started out,” Connie added, “we didn’t realize this was going to be a career – it was more of a professional adventure. That first year we mostly stayed with friends along the way and sometimes slept in the truck. We were able to get by since neither of us spends very much money – we’re both very frugal, and the D’Put doesn’t take much gas. But within the past eight months, we’ve been making enough to live on, and the future looks exceptionally bright. “

The two Folktellers have come a long way – much more than the 60,000 miles registered on D’Put’s odometer – since making that decision to venture into the shaky but exciting world of the free- lance entrepreneur. They have presented over 600 programs, often as many as four a day. They have appeared at Mariposa in Toronto and the Winnipeg Folk Festival – both in Canada, the 24th Annual International Folklore Festival in England, and most recently, at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee. This month they will take part in the Fall Book Fest sponsored by the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. Past appearances have included an all day workshop for the Catholic Library Association in St. Louis and the National Folk Festival at Wolf Trap in Washington, D.C. They have demonstrated storytelling techniques at the New York Public Library and taught courses at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia and at Pace University in New York. In the spring of 1979 they will make a trip to California and plan to perform along the way.

But the story of that long bumpy journey is best told by observing them at a festival . . .

Amid greetings from all sides, D’Put bumps to a stop at the edge of a large clearing in a field at Jonesboro, Tennessee, and the two attractive smiling young women in denim coveralls and brogans hop out. Barbara and Connie lower the tailgate of the camper and begin pulling out armfuls of fascinating props – a six-foot crocheted boa constrictor, a mouse with wings, assorted handmade puppets, an old-time banjo, and several mountain-made limber jacks. Arms filled, they head for the improvised wooden stage to join their fellow performers at the prestigious National Storytelling Festival.

Within a half hour the meadow is jammed with vehicles, blankets, camp chairs, and stools as hundreds of people from all over the country gather to listen, share, and participate in this very special form of entertainment.

The Folktellers begin their virtuoso storytelling performance with a spine-chilling horror story. Then they tell a tale in tandem, cleverly swapping lines and saying some words in harmony. Seeing the two perform in this spoken duet, harmonizing their minds and voices and gestures, one senses a rare comradeship between them. Contrasted with Barbara’s lighter, comic touch, Connie’s delivery reveals such intensity and power that she rivets you attention to her folktale, whether she is shouting dramatically or whispering. In her delivery Barbara changes voices for different characterizations and uses a wide variety of facial expressions and gestures. Connie uses the full range of her voice, with all its lyric highs and somber lows.

The audience does not fail to sense these special traits. They listen spellbound, and when The Folktellers finish their set with a rollicking grandfather tale, the listeners respond with chuckles and guffaws. “Working with young people keeps them constantly on their toes … their enormous vitality and enthusiasm keeps restive preschoolers perched on seat edges- wide-eyed and wondering.” The Folktellers’ bag of tricks includes a six-foot boa constrictor, hand puppets, and dancing “limberjacks”

After the show, the crowd surrounds The Folktellers asking questions, volunteering stories the women “might like to use in their act,” and offering room and board, companionship, and jobs for them on their next visit to the area. This wonderfully warm scene happens all over the country – be it a storytelling event or a folk-music happening. Once, in New York, after the two had introduced storytelling into a traditional music festival, one man stood apart, hesitant to come forward. Connie noticed him and put out her hand to shake his. He took a moment to search for words, and then confessed:

“Listen you two, I want you to know something. When they announced storytelling, I thought to myself, this is a good time to take a break. But you won me! And I want you never to have a second’s worry if you walk out on stage and see some darned fool like me rising to leave his seat, not knowing the treat in store for him. Don’t worry a bit! You just start right in, and he’ll love it, just as I did.”

The two women thank him – he had made their whole week! “After a concert, people are eager to share stories with us,” Barbara says. “Some are pretty disjointed – they’re straining to remember the details, and some tell dirty jokes, not to be crude but just because that’s what they know and they’re dying to share something. Folktelling puts them in that kind of mood.”

The Folktellers share storytelling techniques with Elizabethton, Tennessee teachers and librarians through their workshop, “Creative Outreaches in Storytelling” “Storytelling,” Connie interjects, “is a rare and intimate touching of people’s minds and memories in a special way. It’s a different kind of storytelling we do than what you’d hear on a back porch. It’s changed a bit, once it is delivered from a stage and behind a microphone, but it is still very personal. In so many forms of entertainment today you simply sit back and things are done to you or for you. But in storytelling the listener is very actively involved creating the images from the words. We believe that’s what makes this special bond between the listeners and the tellers. In our Folktelling, we’re trying to restore what television is destroying – the ability to visualize, to use one’s imagination. If I describe a monster to you with claws and wings and a beak that tears flesh, your imagination can soar. Your monster could be quite mild and tame compared to the huge Godzilla gorilla thing lurking in another person’s imagination. The listeners are working right along with the storyteller; both are conjuring up all those mind pictures and the story comes alive.”

She continues, “Since the story- telling images can be so powerful, we are careful in selecting stories for each age group and we try to be sensitive to the fact that younger children can be upset by frightening stories, especially since they can’t crawl up into our laps and be comforted at the end. Sometimes people will say, ‘Kids have seen all that on TV – you can’t scare them.’ But with storytelling, the images are so much more vivid and real. It’s not your eyes doing the work but your mind. When the telling is over, we don’t want a lot of frightened children. Instead, we want them to have rather fond and exciting memories and an intense desire to read tales and tell them.”

“Storytelling is very different from watching TV,” Barbara adds. “TV is a passive one-way means of communication but in storytelling there’s immediate interaction between the person telling the story and the audience.”

How do they start a Folkteller concert? For an assembly of preschoolers through third grade, usually they get the audience into the swing of it by taking them all on an imaginary bear hunt with hand motions to scout things out and sounds of sloshing and squashing through mud. Once the bear is spotted, there’s a frantic retracing of events, which invariably produces giggles of joy. Then they change the tempo by asking the children to stand, open their closet doors to get out their wolf suits, step into them, zip them up, get their ears on straight, open their dresser drawers take their claws out and put them on. Then everyone tries a low roar and a little gnashing of teeth, before holding out their tails to one side so they can sit back down and hear the wonderful story of Max in Where the Wild Things Are. When everyone is in a suitable mood, Barbara produces a large bag (or a sack, if she’s down south) and slowly, suspensefully pulls forth her six-foot boa constrictor to everyone’s delight. The lovable Crictor obligingly undulates into a living alphabet, scout knots, and numbers, while the story twists into the delightful tale by Tomi Ungerer.

Working with young people keeps them constantly on their toes, since flexibility and spontaneity are absolute essentials. The Folktellers move at a fast clip. Their enormous vitality and enthusiasm keep restive preschoolers perched on seat edges-wide-eyed and wondering. Their constantly surprising bag of verbal tricks often ends with a fun-filled question, “Do you know how to get a gob of peanut butter off the roof of your mouth?” (Spoken rather lumpily, as if it were still there). In school programs for fourth through sixth grades, they blend mountain tales with contemporary stories ranging from humor to mild horror. This age is often captivated by stories with a song (cante fables), “hambone happenings” and “good ol’ grand- father tales.”

Which group presents the greatest challenge? “No doubt about it,” Barbara grins, “the super-cool junior and senior high students. They come into the auditorium with a sophisticated swagger, daring us to prove that storytelling isn’t strictly kid stuff. So at these concerts it’s imperative that we grab them by the shirt collars (figuratively) in the first few seconds. That’s a vital time. But we’ve never lost an audience yet, young or old. It may be because we believe in the art, love it so intensely, or because we display professional confidence from the outset.

Once before an adult concert for a thousand people one skeptic cornered us. ‘I don’t want to be rude, but how do you ever keep people’s attention for over ten minutes with something like storytelling?’ he asked. We told him just to give it a try. After the concert, the man stopped us and shook his head, ‘I’m really embarrassed! It’s not how can you hold somebody’s attention for ten minutes – but what can I do to make this enchanting evening last?’ “We hope to fire up their imaginations,” Connie continues, “so that they will not only leave as converts, but will also be stimulated to try telling some stories themselves, and perhaps be excited about taping and preserving their own families’ stories.”

One way the Folktellers reach potential storytellers is to conduct workshops on the concrete techniques and how-to’s of the art of storytelling. But there’s always more to learn. Connie and Barbara pass a lazy summer afternoon on the porch of Ray Hicks’ home listening to the master tale-teller. These sessions, called “Creative Outreaches of Storytelling,” range from one to 30 hours and offer practical, dynamic ideas that educators can use in the classroom the very next day. The cousins show how to work with sock puppets, flannel boards, props, music, creative dramatics, book talks, and other techniques of reaching children through storytelling. In these workshops they emphasize the beauty of telling picture books as opposed to reading them. And how to tell them, word for word, to preserve the author’s rhythm and story line. They have also compiled a listing of their favorite stories with hints on how to tell them.

Would they advise other librarians to become Folktellers? “Yes! If that’s what they love most about their jobs. At school concerts we really encourage children to consider alternate life styles, to think of career options. And we’ve not only got letters from children saying they’ve decided to be storytellers when they grow up, but three adult friends of ours who talked to us at the onset have since left their jobs as librarians to travel as storytellers! We correspond regularly with Nancy Schimmel and Carol Leita, both from the San Francisco area, and with Sharon Luster, a traveling storyteller and clown who uses the stage name of ‘Olio.’ ” And the pace? “When we left the library, our friends were oohing and ahhing over all the free time we would have . . . time to sit by a babbling brook and read, keep a journal, and just contemplate. But since day one, life on the road has been a fast-moving tumble of events … and we have never managed to find that brook, only more and more streams that lead deeper into storytelling. Our life has been filled with rewards but everything has its yin and yang. For us it comes down to just a few negatives. Letters have to be written – even when you are bone tired and your only desk is the steering wheel of D’Put. Weight gain is also a problem, from fast food to home-cooked feasts. And once our camper was broken into and nearly all of our belongings were stolen – including irreplaceable tapes of storytellers. “

Summing up their experiences, Barbara and Connie speak of the many happy times they’ve had . . . lazy summer afternoons on the porch of Ray Hicks’ home on Beach Mountain in North Carolina watching the shifting light and soaking in the words of a master storyteller . . . holding a crowd of passersby spellbound as they performed their storytelling craft on the streets of Greenwich Village in New York City (and getting fifty dollars in donations by passing the hat) . . . being filmed for a special feature on public broadcasting system’s WSJK (a film devoted entirely to the Folktellers’ activities) . . . chuckling over the puzzled took on the face of a man who came to the tailgate of their pickup, slapped down a dollar bill and asked, “Are you a coffee wagon?” . . . and remembering all the people who have fed them and opened their homes to them during their journey.

The itinerant modern-day Folktellers, Connie Regan and Barbara Freeman, may be the precursors of a new wave of librarians who are changing their lives to bring an age-old art back to the people.