- Written by: Barbara Home Stewart – School Library Journal

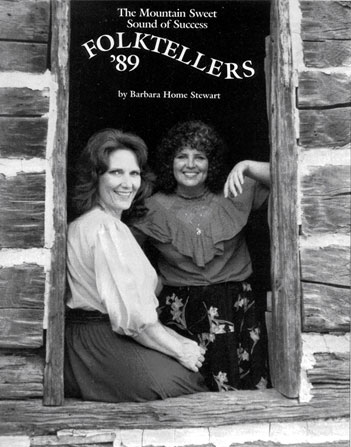

RARELY does life give one an opportunity to disprove the truth of Thomas Wolfe’s tenet that you can’t go home again. But sometimes it does-and when it does, that experience can be memorable, even extraordinary. My return visit after ten years to interview the internationally-acclaimed FOLKTELLERS®, Barbara Freeman and Connie Regan-Blake of Asheville, North Carolina – coincidentally, Wolfe’s hometown-was just such an experience.

But let’s back up a jot. In 1978 I wrote an article about two charismatic and determined young first cousins who had resigned their jobs at Chattanooga Public Library in Tennessee in 1975 to do what no other librarians in this century had ever dared: go on the road as traveling storytellers, without the security blanket of regular pay-checks, medical benefits, even a savings account. With a meager $2,000 between them for expenses, they had piled a wild collection of puppets, quilts, limberjacks, and overalls into the back of a yellow pickup truck of uncertain lineage named D’Put, and headed for parts unknown in search of their new career and lifestyle. When they pulled into my driveway in Philadelphia to ‘audition’ for a group of Delaware Valley librarians at a dinner I had planned, they had already spent three years living in the pickup. D’Put was their office, prop room, dressing room, dining room, and bedroom.

In November 1978, School Library Journal ran my piece about Connie Regan (now Regan-Blake) and Barbara Freeman, under the title The Folktellers: Scheherazades in Denim. It was the first time that SLJ’s cover had ever featured a photograph of people. The readers’ response was overwhelming and re- warding: not only did the piece elicit more letters than any item published in SLJ up to that point, but it also spurred a meteoric rise in the careers of these two intrepid women – and was instrumental in launching a massive renaissance in the world of storytelling.

For a decade the Folktellers kept my interest alive with letters, post- cards, and mementoes – progress reports sent from all over the globe:

- February 1979 (from New York City): “. . . have received over 700 requests for our bibliography, Stories for the Telling – from as far away as Brazil and Iran, plus 250 letters. We’ve had 150 offers for jobs. Can you believe that?! We are still kind of blown away by it all. Some things are going to have to change. I don’t think we can keep up with the volume.”

- March, 1979: “We’re booked for UNICEF benefit and San Diego Folk Festival … have received 1,005 letters, most asking for Stories for the Telling.”

- July 1979 (from London): “It is really something to walk into a foreign library and see ourselves, via SLJ. Lincoln Center for performing Arts coming up this Fall.”

- September 1979: “Betty-Carol Selien of Brooklyn College Library wants permission to use SLJ article in her new book, What Else You Can Do With a College Degree, to be published January ’80 by Gaylord Professional Publications in association with Neal-Schuman Publishers. Will you OK this?”

- November 1979: Dr. James L. Thomas, Carol Lawrence, and Jennabeth Hutcherson are including the SLJ article in their forthcoming book, Storytelling for Teachers and Media Specialists, to be published by T.S. Denison & Co. August 1983: “Great news! We have just cut two albums, White Horses and Whipporwills (Folk Legacy Co.) and Tales to Grow On (Weston Woods).”

- December 1983: “Your troubadours are now in Japan – Okinawa – telling stories at U.S. military bases through the Department of Defense. Had a four-hour, midnight reef walk and have eaten everything from pigs’ ears to octopus.

- “October 1984: “Our third album, Chillers, has been named an ALA Notable Record! We have arrived!”

Throughout this time of soaring popularity, they performed at Folk Festivals in Chicago, Vancouver, Winnipeg, Ithaca, Michigan, Knoxville, Alaska, Long Island, St. Louis, Charlotte, Philadelphia, Maine, Connecticut, Lincoln, and Monterey. Their lively folktales kept audiences applauding at such divergent places as Bele Cher Celebration in Asheville, the World’s Fair in Knoxville, Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park, the International School in Belgium, U.S. Dependent Schools in the Philippines, the Healing Arts Festival in Boulder, CO, the Washington, D.C. Ethical Society, dozens of state library associations, the International Reading Association, and the National Council of Teachers of English. Later, phone calls replaced cards. In 1985, Barbara called to announce: “We can afford to fly and rent cars now and stay in motels – in separate rooms! – instead of sleeping in the back of D’Put. We’ve settled here in Asheville, opened an office and hired a company manager and a staff. Best of all-we’ve started on a new project. We’ve co-written and produced a professional two-act play using our favorite tales. Can you come down to see it?”

It was impossible then. But three years later, in the Spring of ’88, I found myself driving through the mist-shrouded mountains of the Blue Ridge Parkway, heading for the glitzy new Folk Art Center near Asheville to see their two-woman play, Mountain Sweet Talk. As I pulled into the crowded parking lot, I wondered exactly how the two formerly thread- bare Scheherazades in Denim had transformed themselves into off- Broadway (okay-way off-Broadway) stars of a hit production that has sold over 11,000 tickets during its three season run of over 100 performances.

Inside, I picked up my Annie Oakley and stopped to read some reviews that were posted in the lobby. The National Storytelling Journal (Winter 1987) described the play as “daring, brilliantly directed and performed – an evening that grows in the imagination … superb! There are a thousand lovely touches … a story brilliant with movement, mime, laughter and drama.” The Asheville Citizen-Times said it was “an enchanting and completely satisfying production.”

I talked briefly with Jim Gentry, director of the Folk Art Center (he also doubles as house manager), who told me that since the center opened in 1980, Mountain Sweet Talk has been the single most exciting special program in which they have been involved.

I chose a seat halfway up the amphitheatre above the recessed stage and waited expectantly. The faint wail of a mountain strain set a mood of nostalgia: “Take me back to the place where I first saw the light, to the sweet sunny South take me home . . .” Then came the rousing notes of a clog dance (an old mountain form of square dancing) and, suddenly, there Barbara and Connie were in the spotlight, sparks of energy cascading from them like the sparkling contrail of an incandescent rocketship. In moments we fell under the spell of their words as they pulled us – like Doctor Who – through a rotating tunnel of time travel into a simpler era and place, a place where we could hunker up closer to a lighter knot fire in a cabin, or a cave where we could share in the universal mysteries of that ubiquitous shaman, the master teller of stories. With artful direction they lured us into that distant inner space, revealing in us depths of joy and terror, hilarity and grief.One minute we felt the pangs of regret or denial, envy, revenge, even the pale chill hand of death on our shoulders. In the very next story, we kicked off our shoes and luxuriated in the rib-bursting laughter of a mountain Jack Tale – all part of the storytellers’ magic.

After the show, Connie and her husband, Phil Blake, Barbara and her new groom, Mike Vaniman, and I chatted over burgers at an all-night restaurant. It was immediately apparent that these two very attractive men – both strong and stable – were totally supportive of their wives’ endeavors.Mike, who designed and built the sets for the play, grew up in the theatre: his mother was assistant director of the prestigious Palo Alto (CA) Community Theatre. He has been scenic designer for the Brevard Little Theatre and has had leading roles for the Asheville Community Theatre. A machine designer and holder of a commercial pilot’s license, Mike first wooed Barbara with an invitation to go blueberry picking in the mountains. This past November 26, they were wed in a fairytale ceremony at the tiny log cabin they built them- selves high atop Elk Mountain (befitting a true storyteller, they live nearby on Spooks Branch Road).Connie and Phil share her little white artist’s cottage on 44 acres of wild Mountainside. Phil, a real estate appraiser and champion amateur racquetball player and golfer, often handles lights and sound for the play. A native of Asheville, he completed his college credits toward his B.A. in business administration by serving as a full-time magician at the popular Blowing Rock, NC, tourist attraction, Tweetsie Railroad, doing “big time illusions — sawing women in two, levitating bodies, etc.”

Understandably, both of their swains have a vested interest in show business, but it’s extraordinary that both couples get along so famously. “On the very few days off they’ve had during the past three years,” Barbara teased them, “guess where they went? To the play! They study the audience, suggest bits of business we might use on stage, check the music and lighting and generally work the house. And they love storytelling.”

I asked how they accounted for the wide appeal of storytelling, beyond even the scope of the men in their lives.“Storytelling is so personal,” Connie said, “and because of that, it has great power to move people in the same way great music moves them. That’s what draws all people to storytelling – people have always listened to and told stories, so there’s a sense of familiarity. Even if people say, ‘You know, I’ve never heard a story told before,’ the stories seem very familiar to them. Stories take us back to our origins.”There’s a real healing effect to storytelling,” Connie continued, “Once when we were in State College, PA, telling stories to a 4th through 6th grade group, a really strange thing happened. While Barbara was telling a story, my mind kept wandering to my cat, Gingko (I really miss her when I’m away). I felt her sitting on my lap; I was petting her. I couldn’t focus in on Barbara’s story; I began to wonder if something had gone wrong with Gingko – it was such a strong kinetic image!”

After we had finished our set, the teacher pointed out a young boy leaving the room, waving goodbye to us. She said that he had just spoken and smiled for the first time in three weeks. His home had caught on fire; all the family got out but they had watched helplessly through the window as their cat burned to death. The boy had not said a word in three weeks, but when we started our stories, he gave a big smile and turned around to say ‘Aren’t they good?” to the teacher. As soon as she told me about it, I started weeping, because the power had been so strong to me – the feel of my cat safe in my lap. She told us we had given that boy a real gift.”

Barbara also told of an incident that had a strong personal meaning for her. “One night, before the play started,” said Barbara, “I asked Connie to enhance a tender moment by joining me in a duet instead of my singing alone. When we went out on stage, we noticed several handicapped people in wheelchairs seated down front, stage left, where Connie stands.”So I start off singing, ‘in the pines, In the pines,’ and suddenly I hear this booming bass voice singing ‘In da PINES, In da PINES.’ I thought maybe I shouldn’t have asked Connie to join me after all! But it was a man in a wheelchair, singing at the top of his voice. First the audience tensed up when they realized it was not part of the performance. Then they all relaxed as he sang all the verses of the old song right along with us, oblivious to everyone. He was so involved with the performance, it was truly touching.”

Coping with spontaneous outbursts while on stage was one thing; working together to solve problems on the road was quite another. “My method of dealing with problems,” said Barbara “was to let them roll off my back like drops of water until they formed a pond, and then try to drown Connie in it. Her method was to dip in an oar every time a problem came up. So with these two different approaches, we did learn to communicate. Some days we’d cry our differences out, some days we’d laugh ‘em out.”

“Our three-day discussions were lifesavers,” Connie agreed, “life rafts for getting over conflict as we traveled. We became so much better friends after that, and, I believe, better performers. “Usually Barbara keeps them loose by playing the part of the prankster, her ebullient personality and Falstaffian laughter filling the room – and imbuing any situation with hilarity.

The “cosmic pixie” (as Mike calls her) can match extempo wits with the best comedians going when she’s on the run. Occasionally, it created problems on the road until they both learned what was happening.”Once,” Connie said, “a microphone fell apart during a concert. Barbara replaced it and delivered a funny quip, but I found it hard to get the audience back into the mood of my story. So she had to learn to reserve her special humor for her own introductions.”

Connie, ever the intense and serene partner of the team, developed a splendid clarity of tone and purpose during their work on Mountain Sweet Talk. On one hand, her haunting sepulchral tones invoked the pleas of a mother, mistakenly buried alive; whereas the lyrical quality of her lighter moments caused fellow story- teller Jay O’Callahan to write, “If a rose could speak, it would have Connie’s voice.”

They have never missed a performance in 14 years. They came close once when they developed terrible sore throats and head colds before flying from California to Boston to accept the Alice Jordan Award at the New England Round Table of Librarians. While one woman was performing, the other was blowing her nose and hacking away (detached from the lapel mike) and vice versa. But they performed so smoothly, the audience never noticed just how sick they were.Barbara said, “Our most grueling experience occurred in Arizona when we’d just completed a full week of shows at school. We had really over scheduled ourselves and had just struggled through the last show on Friday afternoon, and were packing up our props and were ready to leave the stage when the principal begged us to do just one more 30 minute set for the kindergarten children who had missed the assembly. How we did that show, I’ll never know – but we did. We always pace ourselves down to the last minute, not like some performers who wing it. We know exactly how long it will take for each set, each gig, and we pace ourselves, because our voices and our energy levels have to be recharged, but that day we were literally croaking out the stories. It was the absolute pits. But the kids loved it.

“During the course of our after-theater session, I got a chance to ask them some specific questions:

Who took care of the business while you were on the road?

Connie: “To handle our business affairs we worked out an effective system called ‘Business Week.’ At first, it was ‘Business Day.’ It evolved slowly and from necessity. Every other week one of us had to handle all the necessary telephone calls, record titles of stories we told each place in our master book (to prevent repeats on return trips); record addresses, be responsible for leaving the host’s house on time for the next appointment; leave parties early so we could sleep; plan the driving schedule … and lock up the camper. One perk was that the Business Week person got first choice of beds. This system kept the total burden from falling on one person and also allowed each of us a vacation every other week. It also ensured that each of us learned all facets of the business, not just those that came easiest to us.

“Did you ever get bored from so much enforced – even claustrophobic – intimacy on the road?

Barbara: “Never! We used the CB a lot. My handle was Storyteller; Connie’s was Carolina Gypsy. We learned so much from CB’ers: where the best, cheapest food and gas was, the shortest, safest routes to our destination. We sang, exchanged jokes. Once we even told a story in tandem over the CB to a principal who later booked us for a concert at his school!

“Connie: “And we were always busy on the road, doing correspondence, figuring expenses, organizing our schedules and planning our stories. Seems like we were always singing or telling stories or working on our delivery as the miles rolled along.

“Barbara: “When we started out, we knew of no one who was doing this, so we had no role models. We just started inventing the job of itinerant storytellers as we drove along. In 1975, there were many fine performers keeping the craft alive in libraries, but not traveling the circuit. Others were beginning to hold community concerts, but there was only one Storytelling Festival in the country in Jonesboro, Tennessee. Today, there are 300 professional storytellers and over 50 festivals in 38 states, and we have appeared at many of the first festivals ever held.

“When did you officially become THE FOLKTELLERS®?

Barbara: “In 1975 Margery Nichols, a friend of Bill Domler (he really launched our career), thought it up. Later, we registered it officially with the Copyright Office. Now it’s protected with an “R”, just like a trademark. So many storytellers who heard of us began to use the term folktellers generically, like kleenex without the capital “K.” So now, we write them and explain that they must use another name. After all, before us, there were no ‘folktellers’: we made the word part of the language.”Do you feel your mission has changed since your days of working with children in the library?

Barbara: “It’s a very different life-style. The library was 9-to-5 and involved a lot of paperwork, recommendation of books, and giving book talks all day long. It was dealing with one person at a time except when the school groups came in with 30 or 40 kids. When I came to Chattanooga Public Library in 1971, only 12 children were coming to story-hour. When I left, we had 200 children lining up to get into the castle I had designed in the children’s room. Over a hundred of them had to wait in another room watching movies until the next story hour started.

“But today there may be 20,000 people in the audience, as we had at the Philadelphia Folk Festival and Winnipeg Folk Festival. In some ways, because you’ve put out enough energy to encompass thousands of minds and bodies, it’s more exhilarating but it’s also more demanding than a regular library job. That’s hard for most people to understand, because they think, ‘Oh, you’ve got it made.’ And we do. And I’m not complaining. And yes, it is a Princess job; yes, it’s perfect. However, when you stand up in front of 20,000 people to entertain them with stories, there is some energy going down! You have to deliver!”The library world is very patterned, very Zen. On a traveling schedule, getting to the plane or concert on time may be good stress, but it’s stress nevertheless, and it takes its toll. You can’t work 40 hours a week telling stories, because you wouldn’t have a vocal chord left, and your brain would be pure mush. It’s tough on the road: tough and delightful.”

What projects do you see in the future?

Connie: “Well, one reason for producing our play was so that we could have more time to spend at home. Now, from June to the first of November, we are able to be with our husbands when we’re not on stage. We may one day take Mountain Sweet Talk on the road a week at a time, but we aren’t contemplating a full road tour.”

Barbara: “Somewhere along the line, we want to produce a book on how to conduct storytelling workshops, or how to become a storyteller. Fortunately, we have time on our side. In the world of storytelling age is an advantage; you get better, more credible, as you get older.”

When Connie and Barbara started out in 1975, they gave 1,000 performances in three years, a grueling schedule largely advertised and promoted by word-of-mouth. Today nine people handle the production of Mountain Sweet Talk, their personal appearances, sales of cassettes and records, TV, radio, newspaper and magazine interviews, their travel schedules and their finances. The multi-talented Lindig Hall Harris, a typographer and former theatre manager, directs the office operations from downtown Asheville, keeping the books, and contracting for distribution of flyers, placards and posters. Nancy Orban handles all their publicity.

These days the Folktellers fly to their performances, hire rental cars, stay in motels. This frees them from the demands of their earlier minstrel lifestyle where the host or hostess often expected free improvisational performances (often until the wee hours) in return for bed-and-breakfast or dinner.

No question: these two were pioneers, and pioneers have no competition. But they constantly offer advice and down-to-earth survival information to would-be storytellers, itinerant or otherwise.

Connie: “So many people have told us that our article in School Library Journal made them decide to quit their jobs and become storytellers. We always refer them to NAPPS [the National Association for the Preservation and Perpetuation of Storytelling] for a directory of institutes, workshops, resource catalogs, and folk or storytelling festivals around the world.

“Both Connie and Barbara were in on the founding of NAPPS, which was conceived by their close friend, festival organizer Jimmy Neil Smith, who has helped guide the group to its present size of 2,000-plus members. Both women served on the Board of NAPPS for ten years, actively leading the organization to its new national prominence.When they first came up with the idea of producing a theatrical showcase for their stories in 1985, they contacted a noted writer-director-actor, John Basinger, who with his daughter Savannah worked with them on the script for Mountain Sweet Talk. Now for the first time Connie and Barbara could bring together in a single vehicle their many talents for storytelling, drama, humor, history and research. The play draws deeply on their own ancestry and on the powerful spiritual ambiance of the hills that have shaped their lives as Southerners, the Blue Ridge Mountains of the Carolinas and Tennessee.

In 1987 an event occurred which may send the Folktellers in yet another creative direction. Barbara won a minor role as Mavis the cook in a major motion picture to be released in 1989 – Columbia Pictures’ production of Winter People, starring Lloyd Bridges and Eileen Ryan. Lynn Stalmaster chose Barbara for the role from dozens of contenders. Now agents are already submitting offers to her and Connie for future films.It may sound like all business, but there is a light side. “We do have a good time performing,” Connie said. “We try to convey that, so that we can encourage children and adults in the audience to consider optional careers. Lots of children write us. One letter in particular showed we had gotten our message across. A young boy wrote, ‘My father asked if I wanted to be a storyteller or a fireman. I said a storyteller during the week and on weekends a fireman.’ “Rachel Stein, writing in The Arts Journal, October 1985, perhaps describes best Barbara’s and Connie’s effect on the field: “At the forefront of the American storytelling renaissance, [they] are continually forging the territory, bringing a love of tales to new audiences.”

By creatively and energetically overcoming obstacles and by simply enduring on the road, the Folktellers have carved a new frontier of careers and lifestyles for hundreds of future storytellers. Like great wise resourceful spiders – like Charlotte herself – they have spun iridescent filaments of courage, color, and craftsmanship into a web of literary delight which first attracts, then ensnares and ultimately captures the minds and hearts and imaginations of the viewers.

We all become a part of the warp and weft of the ageless tales they weave. We are truly touched by that simplest of ancient devices: the well-told tale. The fractured fable, the ancestral anecdote, the philosophical parable – all are a part of the storyteller’s stock in trade because they deal directly with the human condition: with affairs of the heart and mind and soul. This is nothing more than direct, powerful, one-to-one communication, undiluted by technical effects, laugh tracks, or TV commercials. It is nothing more than the majesty of simple words conveying fear and dignity, courage and compromise, bitter loneliness and lasting love.

We hear it faint and clear at first, then rising to thunderous force, then fading to a just perceptible graveyard whisper, the melodic strains of the Folktellers weaving their country rhymes and robust jokes, spinning their lilting and unforgettable Appalachian tales.As Stein wrote, “In their stories, the Folktellers have carried a taste of Appalachia far and wide and now the mountains have drawn them home.” Yes, Thomas Wolfe, you can go home again. Even to Asheville, North Carolina.

- SCHOOL LIBRARY JOURNAL/JANUARY 1989

- Barbara Home Stewart is Senior Regional Sales Manager, Institute for Scientific Information, Philadelphia, and a freelance writer.